OUR BODIES ARE NATURALLY HEALTHY AND WANT TO STAY THAT WAY

Seems Like a Miracle

That we rarely succumb to infectious illness is downright miraculous, and our immune systems deserve most of the credit for that. The main function of this diffuse, interacting network of cells and chemicals is to combat pathogenic (disease-causing) microbes. It patrols the body for anything abnormal and potentially dangerous, such as cancer cells.

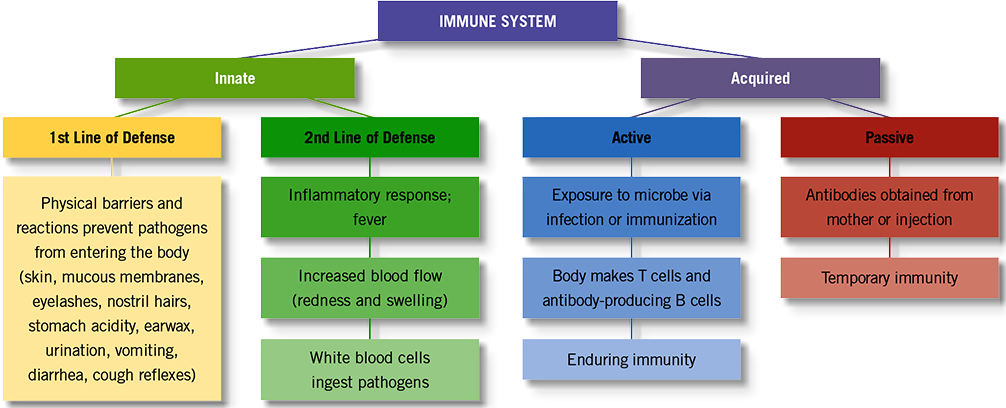

This complex and fascinating system affects your every waking hour, so learning how your immune system works will help you understand your body’s response to infection and shed light on how to boost your immunity. Let’s take a look inside. (See our Immune System chart for more details.)

Divide and Conquer

The immune system has two main divisions: the innate immune system, which needs no previous experience with intruders to dispatch them swiftly, and the acquired immune system, which requires contact and time in order to develop a specific response to a particular pathogen.

Innate. As its name suggests, the innate immune system is in place at birth. It reacts quickly and in a generalized fashion to any foreign invader. Physical barriers and reactions form a key component of this system: Skin and mucous membranes act like castle walls to keep out invaders. Eyelashes and nostril hairs trap dirt, microbes and pollen. Stomach acidity kills many microbes. Earwax keeps the inner ears healthy. Urination flushes out bacteria. Vomiting and diarrhea propel bad microbes from the intestinal tract. The gag, swallow and cough reflexes protect the body’s airways.

A Second Line of Defense

Fever is a second line of defense; it contributes by activating infection-fighting immune cells (“cytotoxic T cells”). White blood cells (called “leukocytes”) form another component of innate immunity. These include natural killer cells (which attack virus-infected cells and cancer cells); cells involved in allergic reactions; and several types of cells (“phagocytic cells”) capable of ingesting abnormal cells and bacteria, and other foreign material.

Antibodies

Some cells release “cytokines” — a large group of chemicals that facilitate communication among cells. Cytokines stimulate or inhibit activity of white blood cells, interfere with viral replication, and communicate with the brain. The brain, in turn, sends signals that influence the immune system and other bodily systems.

Here’s an example: Some cytokines contribute to the “inflammatory response,” the body’s nonspecific response to any irritant, including infection. The body’s characteristic redness, swelling, tenderness and warmth are evidence of increased blood flow and delivery of immunity goods to the site of the irritant. Meanwhile, cytokines also quickly reach the brain, prompting sleepiness to promote rest.

This site and all of its contents are copyright © 2015 New America Inc. All rights are reserved.